I CAN still hear my father scoffing at the impact of television on the British public.

I CAN still hear my father scoffing at the impact of television on the British public. “It’s killed the art of conversation,’’ he would moan, echoing the verdict of most 1950s geriatrics on John Logie Baird’s vision of the future.

(To my young brain, every grown-up was a geriatric, even though I had no idea what the word meant).

Killing the art of conversation? I can’t recall discussing ANYTHING significant with Dad over the entire 24 years we were on this earth together. I loved him dearly but when it came to meaningful conversation, he had less patience than a struck-off doctor (oops, that pun only works verbally).

Dad would have been 103 this year, so presumably he’s not spinning in his grave quite as quickly as he would like to be.

He’ll certainly be horrified at the effect of today’s technological jungle on his great grandchildren.

My own grandkids seem to spend every waking moment with their Facebooks buried in a Google of I-pods, E-pads, computers and multipurpose telephones.

All but the youngest are in a 24/7 relationship with at least one electronic communication gadget. And I bet little Buddy has programmed himself to join them from his third birthday in December.

‘Computers Have Killed the Art of Television’ disease seems to have affected everyone today between the ages of five and 50.

Symptoms are a total loss of eye contact with human beings, plus an inability to speak more than one syllable every ten minutes.

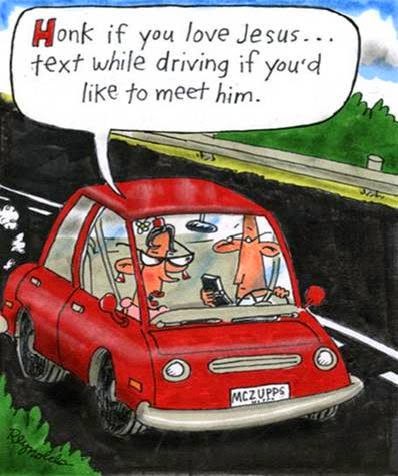

A friend of mine topped it all over dinner the other day when he was so engrossed in online games that he fired off a text message asking his other half to pass the salt.

The bizarre behaviour that is blighting 21st century society is so reminiscent of my own childhood.

The big difference is that millions of people are now living in their own textoxic world, cut off from the reality around them.

Dad’s fears in the 50s ultimately proved unfounded. When I was 10, he was a seemingly ancient 43-year-old - and the goggle box was revolutionising society.

If, that is, you were rich enough to afford a stake in Baird and the Beeb.

Dad, being a reasonably affluent businessman, threw good money after Baird and paid an astronomical price for a flimsy Sobel with a 14-inch scene.

For the equivalent of £2,000 today, the po-faced triumvirate of Kenneth Kendall, Richard Baker and Robert Dougall would catch the tube into our living room and deliver the BBC TV News in a grainy haze of grey and white.

The Beeb’s potted programme package was an alliteration of pretty pathetic pap. But nostalgia plays tricks on the memory and I now accept that The Grove Family was nothing special - just an alternative soap opera to Dad’s bathtime impression of Mario Lanza.